Spontaneous Combustion

Reflections after an unplanned direct action.

Introduction

In the turmoil of the Covid Pandemic, staff and students in Washington, D.C. schools returned to their buildings in August 2021. I showed up to work at a charter school in a neighborhood deep in the Northeastern quadrant of the city. This is a part of the city a lot of folks forget exists. A part filled with rail yards, mechanics shops, warehouses, concrete factories, food production factories, and hospital complexes. There’s also educational workplaces like universities, traditional public schools, charter schools, daycares, neighborhood library branches, school bus maintenance yards, and galleries. Charter schools are particularly concentrated in this area, too.

It was a Title I school where most students came from low-income or middle-income Black and Latinx families. With the Pandemic inflaming an already endless social crisis in the community, the school was in free fall.

Just a few months before I started working there, the Board of Trustees that controls the school switched charter management organizations (CMOs) to a renowned national charter “turnaround” company based in Indianapolis: one of the more than 38 spawns of the notorious Mind Trust, which is often credited as creating the blueprint for privatizing urban education through charterization. Mismanagement, exploitation, and hypocrisy were in the company’s DNA. The company had grown like a cancer until it spread all the way to Detroit, New Orleans, Washington DC and other hot-spots where the charter sector is as big (or bigger) than the traditional public school district.

Previously, the school had been part of a small charter network with two separate campuses managed by a CMO with nearly 30,000 students at over 45 charters scattered across seven states. Its founders made the fortune they started the CMO with as executives in the energy industry. The fallout from financial scandals within the CMO caused the school board to switch to the Mind Trust spawn. They also closed down one of the campuses, leaving the network with just a single school building. Enrollment dropped, and most of the previous staff either left or were never rehired. We started the year with broken air conditioning, which meant it was around 90 degrees Fahrenheit in the upstairs of the building. Students were accumulating new traumas everyday that our school couldn’t handle by ourselves. But no help was coming. The school was on the verge of a death spiral. We had to do something to help ourselves.

An Unplanned Meeting Takeover

The meeting went off the rails when I got a text from one of the Kindergarten teachers. The managers were lying to our faces. Everyone must have gotten the same messages, because my coworkers voices started to rise, their tone grew angry, and they stopped respecting management’s “meeting norms.”Our in-person school year had ended a week before, but management insisted on a virtual “follow-up” meeting. So, everyone dutifully logged on at 10am. The regional director and her crony were waiting patiently. In an act worthy of Broadway, the regional director, with a too-bad-so-sad tone, announced that our principal and assistant principal had “left to pursue other opportunities. There was no one to replace them yet.

Staff, students, and families were already reeling from a traumatic year. So the announcement about the administration team blindsided us. While many of us did not like the principal and assistant principal—or, like myself, believe we could do without them altogether—we all agreed that they cared for the school community. Meanwhile, the company had nearly run the school into the ground through mismanagement and financial profiteering schemes. They fired teachers while we were desperately understaffed, revoked already-earned bonuses for changing jobs, and did shady things to our SPED students to raise test scores. These were only the most glaring of a whole host of issues threatening to overwhelm and destroy the school. So, we were all a little more than suspicious. The atmosphere was tense. A few staff members pressed the regional director for firm answers about our former leadership team—and received dodgy replies. One of the workers then asked: “were they let go, or did they choose to leave?” over and over again. Eventually, the regional director paused for a few seconds, then—finally—said “they chose to leave.”That’s when I, and nearly everyone else, got the text message from the Kindergarten teacher. It was just an image thumbnail. Inside was the principal’s termination letter, sent by the director hosting the meeting. It was too much. Under unbearable pressure, we exploded. One of the special education teachers opened with a salvo about the terrible, contradictory communication and chaos. She ended with: “the 4:30 dismissal time has got to go.”

Our “offer letters” (we don’t have contracts) specified our roles and hours. We all got paid for eight hours a day while the company enforced nine hour days—and most teachers worked longer to barely keep up with the crushing workload. All year, the workers had expressed disgust with these polices. Several times, workers took direct action against them. Most of the time, teachers just refused to do the bullshit busy work admin gave out, and the company couldn’t do much about it because of the shortage of school workers.

Another worker demanded to know if instructional support staff who’d been thrown into different roles, sometimes multiple times a day, would be paid for their extra work. The regional director kept sidestepping our questions. She said to get paid they needed to pull the records from the overflowing group chat, where people begged for classroom coverage all year. Several workers then pointed out that this group chat, owned by the former principal, was deleted. She had no answer for us, and we knew it. Even though we were on zoom, I could feel the rage bubbling up. The school’s social worker then cut the regional director off, “you all have come into a community dealing with immense trauma without thinking about what the community needs at all. Where is the support from this company? We only see y’all once a month!”

This had been something that agitated everyone on the shop floor all year: the company flew a couple of rich white people into the city from thousands of miles away for two days each month, then straight back home. She laid into them for five more minutes.

As she talked, and as several teachers came off mute to support her and launch into their own tirades, I realized this was an opportunity to unite the staff and build power. We’d built up a committee in the first few months of the 2021-2022 school year that took some direct actions. But without a proper formalized structure beyond a group chat, the committee only represented my immediate coworkers, and ultimately dissipated as turnover at our school got worse and worse. It had felt like many workers at the school were content to take it on the chin and keep moving. That was incorrect. A deep rage extended across every grade band and role.

The task I’d struggled with was building a formal committee that met outside work hours. With the help of two external organizers from the IWW throughout the year, I accumulated the knowledge and skills I needed to do that. Even then, each committee we built always slowly dissipated. Here was an opportunity to try again.

I noticed that the Kindergarten teacher had also sent out the image of the termination letter over email to many of us. Several people had already replied expressing outrage and feelings of betrayal.

I hopped into the thread and sent a message venting my own feelings and asking if anyone wanted to form a group chat to discuss how to make change in the workplace. Along with that, I whipped up a google form asking for contact info and platform preference—about ten people filled it out.

Workers are still on the meeting yelling at the regional director, by the way. The meeting was supposed to end by 11:00am. It was now 11:30. Our office assistant in charge of enrollment took the mic.

“The old logo is still on the building, the same color scheme from before, too. How is this company going to support rebranding?”

The director shifted a little bit, seemingly uncomfortable with giving us information about how the company works, “the operations team helps, but really it’s up to the school board.”

The worker shot back, “we need an action item here. You said operations, does that mean the school leadership, the board, or the company makes that decision? I’m leaving so someone else needs to connect those dots.”

She received vocal and written support from staff, and kept pressing her demand until management caved and agreed to weekly meetings with worker input.

Soon, staff members turned to berating management for abandoning us. No counselor, no substitutes, and a stream of overworked, underpaid staff members running for the door had taken their toll. Our social worker spoke out again, “we desperately need a counselor, why do we not have a counselor?”

“It all depends on enrollment, I’m sorry to say. That’s where the funding comes from, and with the school in a deficit, we can’t afford to backfill positions.”

One of the special education teachers—a 26 year teaching veteran not to be played around with—took her turn to criticize not just the company, but the invisible board who hired them.

“I see where they’re all coming from. We felt like the step child of the company, like we were never a part of it as a school community. And it feels like that with the board, too. I feel like they never see the work teachers are doing in the building. We need to let the community back into the building to see what’s going on. We need a commitment to a counselor.”

“It all depends on enrollment…”

Meanwhile, I was setting up our committee’s group chat and collaborating with coworkers to set up the infrastructure to keep ourselves together over the summer. I gathered non-work contacts.

The same special education teacher responded to the director’s vague answers: “We don’t know where any of this information comes from! Why is there no money? Are we non-profit or for-profit? I know y’all probably came into this city thinking this was a hot money making market for you with all the charter schools. But you don’t seem to realize that these other charter companies at least offer more resources.”

I called the company out for doing nothing to cover the school’s deficit. Enrollment numbers had dropped over the pandemic, meaning less funding from the city government government while expenses rose. The regional director and I got into an exchange where she tried to evade my questions, and I kept bringing up my same points. She fell back to the same “it’s up to the board, government, and enrollment,” line, so I went back on mute to allow others to speak.

A teacher and a para-educator aired grievances about being thrown around into different positions with no warning. At that point, it was noon, and the regional director claimed she had another meeting she had to join. I wonder what she said about us afterwards.

Lessons Learned

There are a few lessons to be learned from this action and subsequent events. I reflect on this campaign a lot. Even though we failed, I took these lessons forward with me and applied them to my current workplace organizing campaign. And more importantly, many of my former coworkers brought them to other charter schools, as well.

- Having a formal committee that’s representative of the workplace is essential. Consistent one on one organizing conversations between workers is the best way to build one.

- Spontaneous direct actions by workers can win some gains and catalyze the creation of an organizing committee.

- However, without immediate follow-up one on one conversations and a solid collective culture, organizing committees will dissipate.

- Unplanned direct actions lack the focus needed to win bigger demands.

- Inoculation is key. Without solid inoculation and leadership from an organizing committee, workers can lose heart and resort to more immediately confrontational, individualist direct actions that only invites retaliation with no benefit to collective worker power.

During the 2021-2022 school year, my coworkers and I were able to win certain concessions from management through loosely coordinated direct actions. For example, our ex-principal imposed an attendance policy that collectively punished the staff for the late arrivals of only a few (and those workers were only late consistently because of terrible conditions). Throughout the next day, groups of workers would go down to the office in waves to protest—spurred on by everyone else cheering them on.

We won.

Even so, most of the tangible organizing only happened in my department—the 3-5th grade instructional team—and the middle school instructional team. Within our own circles, we were strongly critical of the principal. Eventually, one of the 3rd grade teachers even lead us in writing up a formal complaint against them. But after consolidating a committee representing K-2, 3-5, para-educators, and food service staff, I discovered there was a significant minority of staff who loved our principal and assistant principal. The two of them being fired was what agitated them enough to take action and join the committee in the first place. And thinking back on it, the two of them actually did a lot to stick up for us against the company, which is probably why they were fired in the first place. Without a formal workplace-wide committee, we couldn’t see that. I had to readjust my perspective.

Our spontaneous actions made a difference. That year, we had an (official) eight hour workday, more robust curriculum support, and a seemingly much more competent leadership team. Less concretely, management was much more careful around us, for a short time. Without a consistent organizing committee to coordinate our actions throughout the previous school year, we never focused our demands. As cathartic as the meeting takeover was, it was largely a group venting session consisting of a grab bag of grievances. The regional director only concretely followed up on the rebranding issue—and that was to convene a committee of employees, putting more work on the plates of those who volunteered—while totally ignoring the more urgent demand for a counselor. Without the proper focus, we weren’t able to build the power to withstand the union busting that followed.

The situation degraded rapidly. Exhausted from the previous school year, I had done little to cohere the organizing committee over the summer break. No one else had, either, but I don’t blame them. I was still the “main” worker-organizer, undermining our collective culture. We did meet a couple times during the “in-service” professional development weeks before the year started, but people started tuning out when the kids came into the building. We stopped having any sort of one on one conversations. That meant our committee became disconnected from the rest of the workers, especially those outside of our own departments.

At that point, the new administration team showed their true faces. Workers got bullied and abused for the smallest mistakes in front of their classes by the principal. The assistant principals would barge into your classroom to observe and “evaluate” how you were teaching. If they didn’t like you, they would slap you with the lowest ratings they could get away with. Agitation went way up, but there seemed like no way to cohere it towards organized direct action that could build real union power in our workplace.

With the previous committee effectively disbanded, I tried to have one on one conversations with more openly militant coworkers to build a new one. But everyone I talked to was so burnt out that setting aside time and energy for an organizing campaign seemed impossible to them. We had become trapped within the confines of defensive, spontaneous collective actions by staff. That’s not to say these were totally ineffective. Staff struck down some horrendous policies and drove the abusive principal to resign two weeks into the school year. But the only person I could consistently count on to help get people organized was a single fellow teacher who I had become friends with. While the two of us were a pretty formidable team, we were no match for the retaliatory power of a multi-million dollar corporation spread across several states.

The hammer came down on those of us singled out as obvious workplace leaders and agitators. We were some of the primary targets of abuse from above. The two of us, along with a handful of other atomized workers, began to get hostile and defiant towards our bosses. Getting screamed at and written up were the usual consequences. Other folks were just fed up. They quit and went to different schools. Almost 20 out of a staff of 60 left by the end of the second month. At the beginning of November, I followed them. My mental and physical health collapsed, so I quit, and went to work for a different school. The organizing campaign withered after that, and the school went into a death spiral. Recently, it finally closed permanently.

Our experience here is also instructive in the perils of organizing in so-called “hot shops” where agitation among the workers is at a fever pitch for long periods of time. In an individualist culture like the United States, people often prefer to quit and seek a better job rather than stick around and organize where they are. All of this was magnified by the then-ongoing “Great Resignation,” which saw millions of workers quit and change jobs. Those who stick around are drowning, constantly, and can struggle to find the breathing room to organize.

It also highlights the necessity of well planned direct actions carried out by organizing committees alongside spontaneous outbursts of worker resistance. During a period of high tensions between workers and management, one of the informal committees we had formed was planning to speak out about our working conditions and student learning conditions at a Board of Trustees meeting. But a couple of coworkers were concerned that we were moving too fast towards that type of action and convinced us that we should have more one on ones to bring a larger crowd of supporters to a future Board meeting. Honestly, it was understandable why we chose to postpone our action, but it was a mistake. We all got busy again and lost track of the one on ones we were supposed to have. People quit. Once again, the organizing committee slowly dissolved. Every so often, I wonder how things would have gone differently had we done that action while we had the momentum.

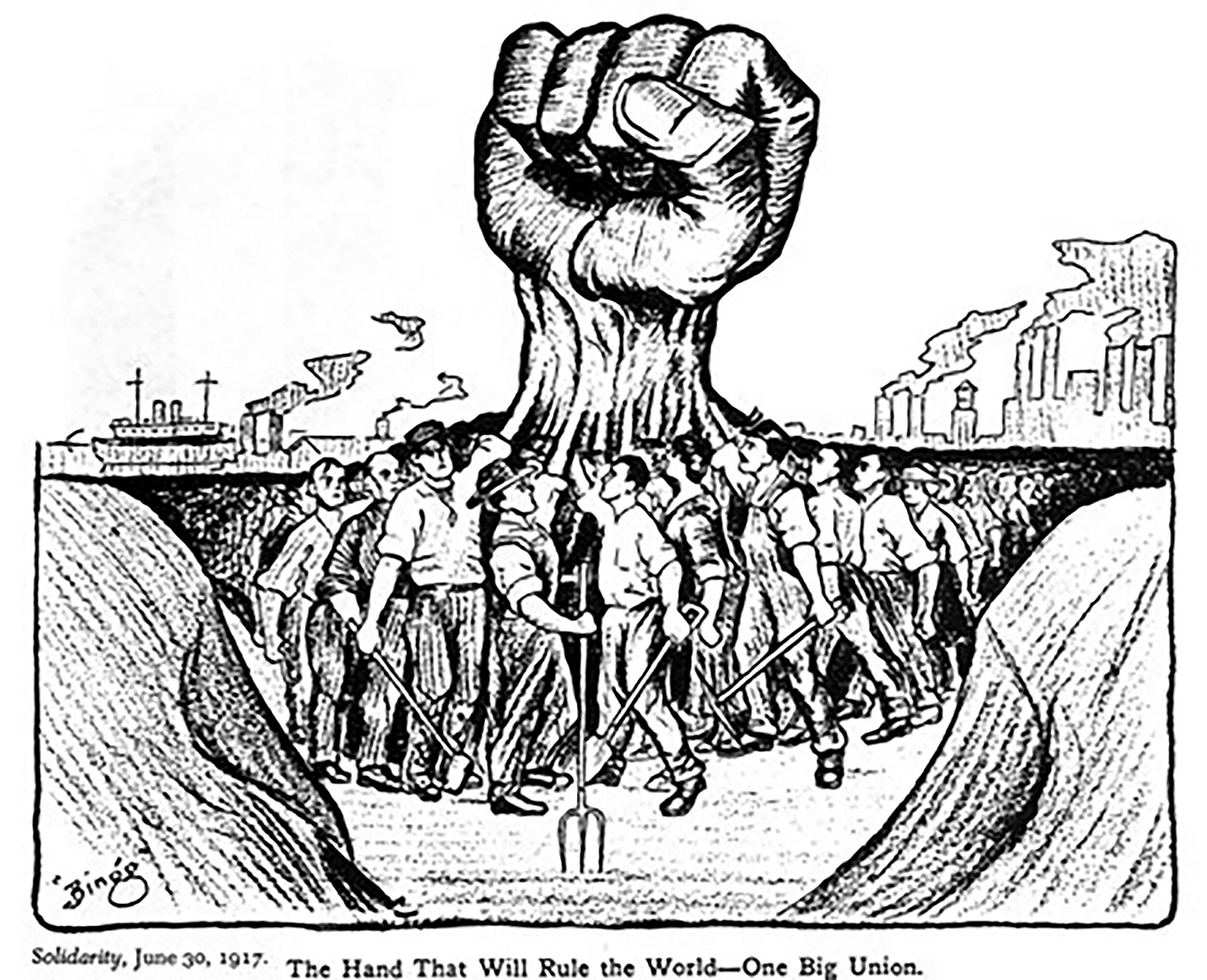

Unionizing charter schools is a risky, dangerous struggle. Charters were created from the racist soil of “massive resistance” to desegregation specifically to destroy teachers’ unions and privatize public education, as revealed by researcher Noliwe Rooks in her book Cutting School. From big companies and non-profits to small networks and single sites, charter schools are some of the nastiest union opponents there are. But it must be done. To defeat the education privatizers, we must defeat capitalism itself, charter school workers must stand shoulder to shoulder with organized workers in public schools. Only then can we raise the possibility of fusing our fractured education industry into a truly public and democratic system. An industrially organized union of all education workers is the best organizational vehicle for achieving this objective.