In Search of "Lady Labor Slugger" Margaret Haley

Reflections on my journey to Chicago, arguably the birth place of American teacher unionism.

We’ve got quite a few projects coming in 2026 that we hope you’re excited about, including:

- Workers’ inquiries on educational workplaces in the Washington, D.C. region including schools, universities, museums, libraries, preschools, and more.

- Further installments of the Industrialization of Education series, this time focused on libraries and museums.

- An analysis of pedagogical machinery, drawing on Marx’s Capital and using case studies specific to educational workplaces.

And other pieces about labor theory and strategy we haven’t planned for yet!

I rarely talk about myself or my personal life on By and for Angry Education Workers. And that’s by design, because this project isn’t about me. Even when a post on this site is written entirely by me, it’s almost always the product of countless conversations with coworkers and other worker-militants spread throughout the global labor movement. Though it’s been a minute since I’ve actually done this, I often workshop the drafts with them, too. All that is to say, when you read an essay by Angry Education Workers, you’re not getting a whole lot of my individual voice, so to speak.

But today is an exception, because during the fall I took a trip to Chicago that I think is worth talking about on this platform.

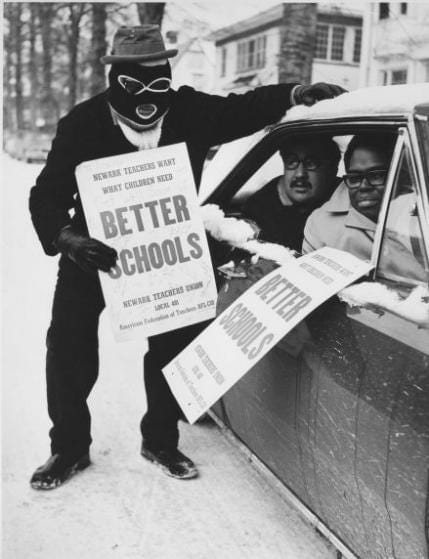

The Chicago branch of my union, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was hosting the Organizer Training 101, and I’d volunteered to be one of the trainers. It’d been over a decade since I’d last visited the Windy City, and since the union reimburses trainers for most expenses it was a wonderful excuse to take a vacation to go teach about workplace organizing. While the training sessions themselves are long and energy intensive—lasting two consecutive days, from 9am to 5pm each day—I had a lot of time outside of them to just kind of wander around the neighborhood I was staying in and the city more broadly. During one of those empty times, I went in search of Margaret Haley, one of the first teacher unionists in United States history.

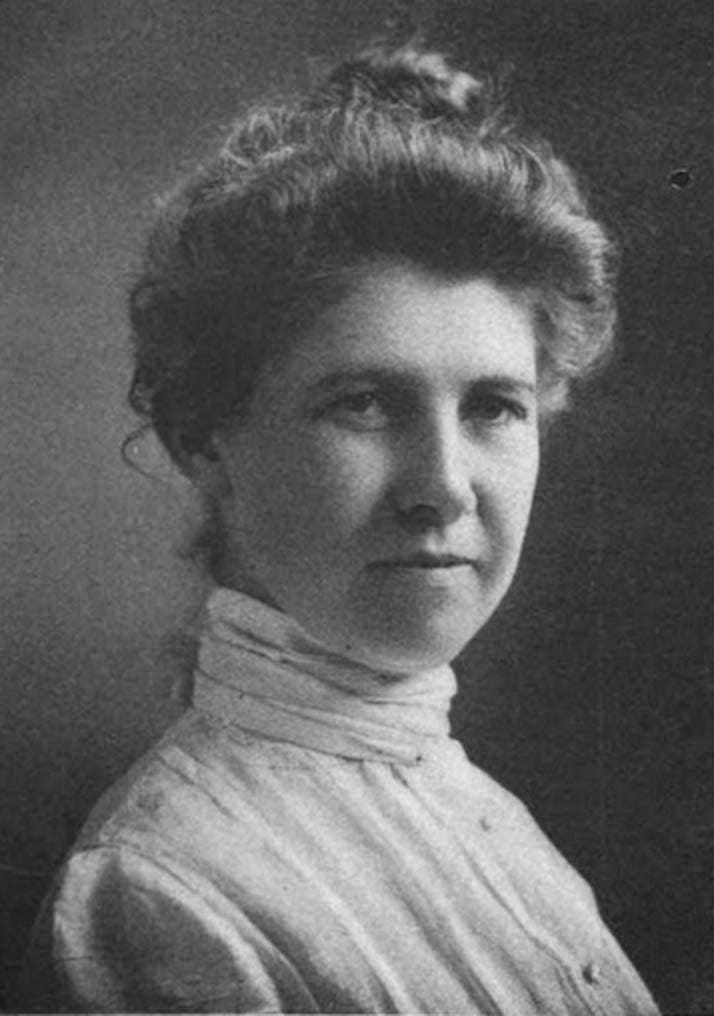

Margaret Haley was one of the founders of the Chicago Teachers Federation (CTF) in 1898. She was instrumental in persuading the rank-and-file of the CTF to formally affiliate with organized labor in 1902.1 That was a decision with tremendous historical significance: one that cohered a significant minority of teachers around a politics of class struggle and disaffection from notions of professionalism, a minority that would explode into a majority during the 1960s.

In 2020, I was studying to be a teacher. My life was one (or more) crisis after another. I was broke, severely mentally ill, and undergoing a process of exile from my family of origin. A degree in political science wasn’t getting me very far in a city flooded with people holding similar credentials but better connections and a willingness to lick the bottom of any dress shoe for a chance at advancement. To get by, I kept working a mix of minimum wage jobs after I graduated—usually multiple at a time. So, I did what many downwardly mobile workers with a degree and little ambition have done for many decades: I decided to become a teacher.

Part of my decision was motivated by a desire to place myself on the front lines of class struggle. In 2018, I’d followed the Red for Ed Strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona with awe. The next year, I joined the IWW shortly before I started my teacher preparation program. A year into it, I took a class that required us to write a research paper about a topic relating to education. I naturally chose to write my essay about the history of teachers’ unions (this was the original version of “Proletarians or Professionals”). As I dug into the history, one of the first things I discovered was Margaret Haley’s speech at the 1904 convention of the National Education Association (NEA), titled “Why Teachers Should Organize”. If you’ve subscribed for more than a few months, you’ve definitely read some quotes from this speech.

It’s an exhilarating speech just to read, let alone experience. Haley was “by all accounts a gifted speaker” who “spoke rapidly and extemporaneously, with great animation” about any issue she turned her attention towards.2 She explicitly called out the business magnates and their political cronies who were always trying to rob the school system, limit the opportunities of working class students, and push schools to operate like factories. Her speech itself was an act of labor activism. For the first hundred years of its history, the NEA was a professional association whose leadership was dominated by male school administrators, college professors, and university presidents. Meanwhile, the rank-and-file were mostly women school teachers who were expected to simply execute the male leadership’s directives.3

Unfortunately, her activism within the NEA would not have much immediate affect. But it paid off in the long term. By the end of the 1960s, rank-and-file teachers chased the male, bourgeois leadership out of the organization and transformed it into a real union. Today, the NEA is the nation’s largest single union, representing not just lead teachers, but all kinds of instructional staff in schools. On the other hand, Haley was instrumental in the formation of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) in 1916.

But before all that, Haley spent decades as a humble, nearly anonymous school teacher. Born in Illinois in 1861 to Irish immigrants, she lived through one of the greatest expansions of public schooling in United States history. She started teaching in rural one room schoolhouses in her late teens, without even a full high school education, to help support her struggling working class family (though she would eventually continue her education throughout her life). Eventually, she was drawn from the Illinois countryside to the rapidly expanding city of Chicago, where she taught at the Hendricks School from 1884 through 1900, when she was elected business manager of the CTF. Her teaching career was characterized by an exuberance for progressive, student-centered pedagogy. Haley embraced every opportunity to advance her pedagogical practice she possibly could have, and implemented these ideas in a school located in a working class neighborhood where she also lived in or near. 4

That neighborhood was called “Packingtown”, an “expansive industrial neighborhood of factories, animal yards, slaughterhouses, grain elevators, iron mills, slag heaps, and coal piles, bordered by huge clay holes which the city used for garbage dumps”.5 Key to the economy of the area was the Union Stock Yard right by the slaughterhouses and meat packing plants. When Haley worked there, the neighborhood received an influx of “unskilled” Eastern European workers. My own ancestors on my mother’s side of the family arrived in the United States during this time period, but instead settled in Western Pennsylvania. Some would eventually migrate to Detroit to work in the auto factories, and then spilled out west all the way to California as deindustrialization foreclosed countless middle class futures. These days, most of them are truckers, teachers, food service workers, or other working class occupations.

Like Haley, I work and organize in the working class neighborhoods of my city. Unlike Haley, I’ve been siloed—against my will—into working for charter schools, which have only existed since 1992. In that way, we actually share a hidden similarity, because the situation in most charter schools is just like that of public schools before widespread unionization from the 1960s-1980s.6 I hope that I am as passionate about student-centered, progressive pedagogy as Haley was. Being a Social Studies teacher in a district where my subject isn’t included on the state standardized testing, I have a lot more freedom to actually teach. Even then, I still deal with a substantial load of mandated testing, out-of-touch curriculum, useless ed-tech platforms, and other forms of deskilling. I can feel myself becoming “an automaton, a mere factory hand” in real time.7 Haley spent her life combating this class offensive by the rich to impose industrial capitalist social relations on the school system.

All that is to say, I had to go looking for whatever traces of Margaret Haley I could find while I was in Chicago. There’s not many. The Unity Building that once hosted the CTF’s headquarters was demolished in 1989, while the CTF itself ceased to exist by 1968. But the Hendricks School still stands to this day. So, after the training wrapped up on Sunday, I decided to take a pilgrimage to the school Haley spent sixteen years working at day in and day out. I took the red line of the L Train to the 47th Street stop and walked the remaining half mile through the neighborhood.

The original building, constructed in the 1880s, was renovated and replaced in 1953. In addition, it is now called Hendricks Academy. Even so, today it stands as one of the few visible monuments to Haley’s life and legacy. The neighborhood around the school is nearly completely different from how it was when Haley taught there. There are no more stockyards or factories. Today, it’s nearly entirely residential. What hasn’t changed is the city government and business elite’s neglect of the community. By 1945, most residents of the neighborhood were Black Americans, a third of whom were promptly displaced by the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway. Union Stock Yard closed in 1971, made obsolete by the dominance of highways and the decentralization of the meat industry.8

Some photographs of the Hendricks School building on the South Side of Chicago.

Fuller Park’s population has cratered to just 17% of what it was in 1950, with less than 3,000 people living there today. In 2013, it had Chicago’s highest “hardship index” based on 2010 census data with the “second-highest percentage of households below the poverty line (55.5 percent), the highest unemployment rate (40 percent), and the second-lowest per-capita income”.9 In the face of this abandonment, residents have banded together to do things like create the Eden Place Nature Center in 2003—transforming a dangerous vacant lot and dumpsite into a hub of community environmental learning. Nearby schools, in particular, seem to visit the most, and the Hendricks Academy is basically right next door.10

A couple snapshots of Eden Place.

That said, I have two major criticisms of Margaret Haley that prevent me from truly admiring her. First, she was a racist. She came from a strongly pro-Union, anti-slavery family, but “was profoundly ambivalent about African American political and economic rights, and she championed the cause of working-class whites—especially the Irish Catholics—over any other group”.11 This is a disgraceful stain on her legacy, even more so because she identified as a socialist. But unfortunately racism is rife among white workers, something that we white folks who identify as radicals need to seriously apply ourselves to solving.

Second, her tunnel vision on elementary school teachers,12 which led her to embrace a craft based organizing strategy in line with the American Federation of Labor’s (AFL). Dividing workers into different unions based on their job role—not even getting into its history of blatant discrimination and collaboration with imperialism—weakens all of us and denies that a fundamental conflict between workers and bosses exists.13 Workers must organize by industry.

Final Thoughts

Haley left very little record of her life outside of her organizing, even in her autobiography. She died in 1939 penniless and forgotten by many teacher-organizers. Finding information on her has been a years long process, involving pretty arduous research just to find a few tidbits of information here and there. There is only one full-length biography about Haley, Kate Rousmaniere’s Citizen Teacher, and I’m pretty sure it’s been out of print for twenty years. It took me awhile to track down a physical copy, though luckily it’s also on Internet Archive.

I came away from my short time in Chicago rededicated to workplace organizing, my work as a Social Studies educator, and to taking better care of myself. The work that all of us do is what makes all of society run, and if we stop, the world stops. We are nothing, but we should be everything. Margaret Haley, despite all her deep flaws, understood that. We can learn from the mistakes her and her contemporaries made and build a better world.

We have power. It’s time we started using it.

For those who made it all the way to the end, I wanted to share with you a teaching guide focused on analyzing Haley’s “Why Teachers Should Organize” speech as a primary source. It’s by Jon Shelton, Associate Professor of Democracy and Justice Studies, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, whose book Teacher Strike! Public Education and the Making of a New American Political Order I highly recommend.

I also got some photos of some awesome murals in the neighborhood that I was staying in that some of you might appreciate.

Much love to Chicago!

1 Rousmaniere, Kate. 2005. Citizen Teacher: The Life and Leadership of Margaret Haley. State University of New York Press.

2 Ibid.

3 Lyons, John. 2008. Teachers and Reform: Chicago Public Education, 1929-1970. The Working Class in American History. University of Illinois Press.

4 Rousmaniere, Kate. 2005.

5 Ibid. Page 20.

6 For a detailed description of conditions for Washington, D.C. teachers before unionization, see Easterling, Christine. 2013. A Giant for Justice: Inspirational Biography of William H. “Bill” Simmons III. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

7 Haley, Margaret. 1904. “Why Teachers Should Organize.” Journal of Education 60 (13): 13.

8 Stockwell, Clinton E. 2005. “Fuller Park.” In Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago History Museum and the Newberry Library. https://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/490.html; Pacyga, Dominic A. 2005. “Union Stock Yard.” In Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago History Museum and the Newberry Library. https://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2218.html.

9 Moser, Whet. 2013. “The Geography of Economic Hardship in Chicago.” Chicago Magazine. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/The-312/May-2012/The-Geography-of-Economic-Hardship-in-Chicago/; Moser, Whet. 2013. “Chicago’s Most Depopulated Neighborhood Is Also Its Most Troubled.” Chicago Magazine. Accessed January 4, 2026. https://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/The-312/May-2013/Chicagos-Most-Depopulated-Neighborhood-Is-Also-Its-Most-Troubled/.

10 Tribune, Chicago. 2011. “Eden Place Nature Center Serves as Model for What Urban Communities Can Do with Vacant Land.” Chicago Tribune, April 25. https://www.chicagotribune.com/2011/04/25/eden-place-nature-center-serves-as-model-for-what-urban-communities-can-do-with-vacant-land/.

11 Rousmaniere, Kate. 2005. Page 5.

12 Ibid.

13 We lay out a fuller critique of the AFL and unions like it in the first part of Towards a Revolutionary Union Movement.